Behavioural presentations shown by cats

From the cats’ perspective, these behaviours are often either normal species behaviours

The fact that many behaviours shown by cats are perceived by owners as problems because they impact on their lifestyle, household or routine management of their cats. From the cats’ perspective, these behaviours are often either normal species behaviours that are finding an outlet in a domestic environment, or behaviours that the cat has learnt to display either to avoid a perceived threat or to achieve a valued resource. In investigating such problems, it is essential to approach each case as an individual ‘story’ and work out why a particular cat started to show a specific behaviour, and how it may have become altered or reinforced over time because of changing events in its environment, such as the behaviour of the owner.

Roaming

Cats sometimes disappear from their homes for long periods, causing their owners a great deal of distress. These absences may be due to hunting trips, an entire male or female cat searching for mates, being trapped because of human activity (e.g. in a garage), or perhaps having difficulty getting back home through the territory of another cat. In some cases, cats permanently move away to another area or house, becoming effectively lost to their owners. Where cats are identified, owners may repeatedly attempt to pick up their cat and return them home. Cats will generally choose to move away from their core area if they no longer perceive this to be safe. This may result from a single traumatic event, or chronic anxiety about aspects of the environment. Finding another location that proves to be safer and more suitable as a core area is often also a factor. Moving from one site to another may be sudden or gradual: in the latter case owners may report that their cat has spent progressively less and less time at home, and ultimately has not returned home at all.

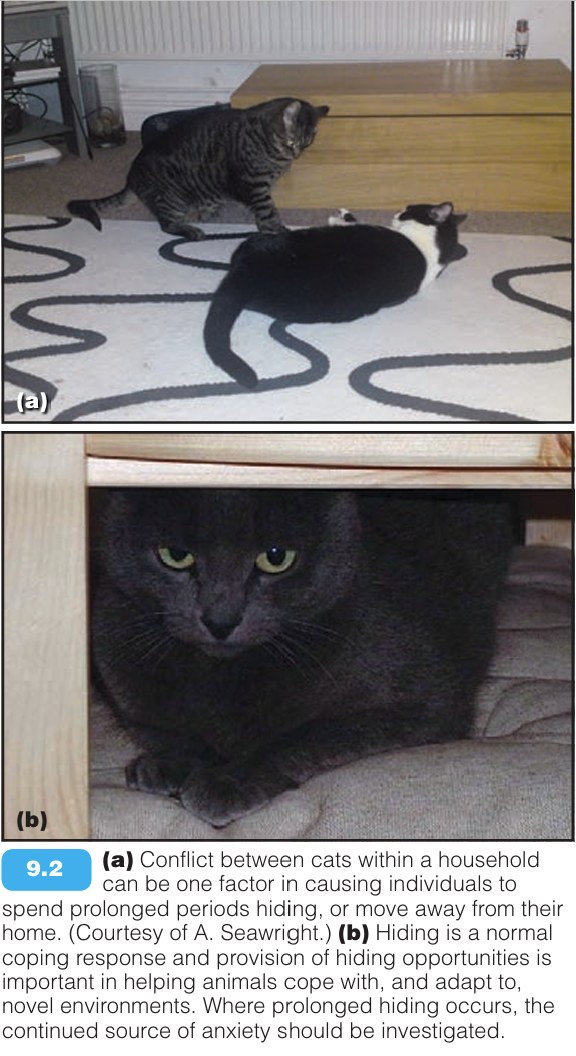

A common factor in cats moving core areas is the presence of other cats in their original home, in either the same household or neighbouring households. Dispersal of cats is a normal response to increased population density, and migrating to a new territory is likely to be perceived by the cat as a better option than being constantly anxious about the threat of other cats or some other source of specific fear or anxiety in its original home.

Hiding

Owners may also become concerned when their cat spends excessive amounts of time hiding or avoiding interaction, particularly if this is a change from their normal behaviour. Withdrawal and hiding (Figure 9.2) is a normal and common behavioural response to a perceived threat (Casey and Bradshaw, 2005). By finding a hidden away or high place to avoid an aversive situation, cats are able to ‘cope’ better in their environment. Hiding behaviour in a rescue shelter environment results in reduced behavioural (Kry and Casey, 2007) and physiological (Hawkins, 2005) measures of stress. As with roaming, cats will hide for extensive peri ods if there is an aspect of their home environment that causes them anxiety, or where they have a spe cific fear response to something present in their envi ronment for prolonged periods. Cats that are fearful of unfamiliar people, for example, may spend prolonged periods hiding whilst visitors stay in the owner’s house. Anxiety caused by unpredictable activity of other cats, not perceived as part of the same social group, may also lead to prolonged hiding. It is important to remember that, although hiding and roaming are perceived as problems by owners, these behaviours are actually resolutions for perceived problems by cats themselves. Hence, merely preventing cats from showing these avoidance responses is likely to compromise welfare further.

Predatory behaviour

The cat is a specialized solitary hunter, with sensory as well as behavioural attributes attuned to this function (see Chapter 4). Indeed, the reason why the cat became a domesticated species is likely to have been due to its hunting prowess, making it somewhat ironic that many people now find the consequences of its hunting activities distasteful. The effect of cat predation on populations of birds and rodents is widely debated (e.g. Woods et al., 2003). Whilst this should be a concern, it is also important to note

that hunting is a natural behaviour for the cat, for which some outlet must be provided. Hence, cats that are restricted from hunting, such as indoor cats, will still be motivated to show predatory types of activity, which need to be directed into play (see Chapter 19). Since cats still maintain the drive to hunt despite satiety, purely ensuring that a cat has plenty to eat will not necessarily stop predatory behaviour (though a hungry cat will tend to increase the amount of time spent hunting). Cats that are not hungry will still hunt, but not eat their prey. Although it is often assumed that young cats hunt more, this is not necessarily the case: Peachey and Harper (2002) found no effect of age on hunting behaviour.

Attention-seeking behaviour

Attention-seeking behaviours are those that a cat has learnt are successful at achieving an owner response, which it perceives as reinforcing. Only 3% of a population of 61 cats referred to a university behaviour clinic had attention seeking as the owners’ primary complaint (R Casey, unpublished data). In a general population survey, 45% of 113 owners reported that their cats showed one or more attention seeking behaviours, though only 6% of these perceived the behaviour as a ‘problem’ (R Casey, unpublished data), suggesting that these behaviours are widely tolerated by owners. Since cats need to be motivated to achieve owner attention, only those cats that value social contact with their owner will learn attention-seeking behaviours. Attention-seeking behaviours can be very variable in form, depending on what each cat finds will achieve a response. Like dogs, many cats will have a range of different behaviours, which they use in different circumstances and in response to different discriminative stimuli. For example, a cat may gain attention by jumping on the owner’s lap when they are sitting down, but need to climb up their leg to get a response if they are standing talking on the phone. Cats are often very good at identifying behaviours that owners cannot ignore, and which always ‘work’ by achieving a response even when the owner is occupied with something else. For example, an owner might find a particular pitch of their cat’s vocalization very annoying or endearing, or always needs to react when the cat walks along the mantelpiece wobbling their best china vases. Although less common than in dogs, cats might solicit attention when they are anxious about other events in the environment. This occurs where owners have previously responded to signs of anxiety by giving their cat ‘reassurance’. Cats can also gain owner attention to achieve specific resources, such as food, or being let out of the house.

Inappropriate play

Playing by cats may be inappropriate because it occurs at an unwanted time, or in an unwanted context, or because the play is rough in nature and causes injury. Interactions between cat and owner are strongly influenced by learning outcomes; hence, where cats value social interaction, including play, the types of behaviour that achieve interaction will be reinforced and thereafter more likely to occur. For example, if owners ignore their cat when it brings a toy, but respond when it jumps off the kitchen work surface on to their shoulder, the cat will differentially learn to show the latter behaviour. The nature of play behaviour is strongly influenced by experiences in the developmental period. In kittens, play is considered to be partly a mechanism for developing and refining the appropriate motor skills for predation (Bradshaw, 1992). During this period, they are also likely to be learning about suitable substrates for these behaviours. Initially, kittens will play with any objects around, such as leaves and twigs, but the queen will direct these motor sequences to the appropriate substrate by returning with prey items. It is likely, therefore, that inappropriate play with kittens, such as waggling fingers on the back of the sofa, may lead to the establishment of play routines in adults directed at humans

Further readings

- Horwitz, D. F., & Mills, D. S. (Eds.). (2009). BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Behavioural Medicine (2nd ed.). British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

- Bradshaw JWS (1992) The Behaviour of the Domestic Cat. CAB International, Wallingford

- Bradshaw JWS, Bale V and Casey RA (2002) Pica in Siamese cats: association with other behavioural abnormalities. BSAVA Congress Scientific Proceedings, p. 609.

- Bradshaw JWS, Neville PF and Sawyer D (1997) Factors affecting pica in the domestic cat. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 52, 373–379

- Calvera M, Thomas S, Bradley S and McCutcheon H (2007) Reducing the rate of predation on wildlife by pet cats: the efficacy and practicability of collar-mounted pounce protectors. Biological Conservation 137, 341–348

- Casey RA and Bradshaw JWS (2005) The assessment of welfare. In: The Welfare of Cats, ed. I Rochlitz, pp. 23–46. Springer, Dordrecht

- Casey RA and Bradshaw JWS (2008a) Owner compliance and clinical outcome measures for domestic cats undergoing clinical behaviour therapy. Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research 3, 114–124

- Casey RA and Bradshaw JWS (2008b) The effects of additional socialisation for kittens in a rescue centre on their behaviour and suitability as a pet. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 114,196–205

- Casey RA, Vandenbussche S, Bradshaw JWS and Roberts MA (in press) Reasons for relinquishment and return of domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus) to rescue shelters in the UK. Anthrozöos

- Fitzgerald BM and Turner DC (2000) Hunting behaviour of domestic cats and their impact on prey populations. In: The Domestic Cat: the Biology of its Behaviour, 2nd edn, ed. DC Turner and P Bateson, pp. 152–175. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Hawkins K (2005) Stress, Enrichment and the Welfare of Domestic Cats in Rescue Shelters. PhD Thesis, University of Bristol

- Heath S (2005) Behaviour problems and welfare. In: The Welfare of Cats, ed. I Rochlitz, pp. 91–118. Springer, Dordrecht

- Heidenberger E (1997) Housing conditions and behavioral problems of indoor cats as assessed by their owners. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 52, 345–364

- Houpt KA (1982) Ingestive behaviour problems of dogs and cats. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 12, 683–692

- Kry K and Casey RA (2007) The effect of hiding enrichment on stress levels and behaviour of domestic cats (Felis sylvestris catus) in a shelter setting and the implications for adoption potential. Animal Welfare 16, 375–383

- Latham NR and Mason GJ (2007) Maternal deprivation and the development of stereotypic behaviour. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 110, 84–108

- Morgan M and Houpt KA (1990) Feline behaviour problems: the influence of declawing. Anthrozoös 3, 50–53

- Nelson SH, Evans AD and Bradbury RB (2005) The efficacy of collar mounted devices in reducing the rate of predation of wildlife by domestic cats. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 94 273–285

- Peachey SE and Harper EJ (2002) Aging does not influence feeding behaviour in cats. Journal of Nutrition 132, S1735–S1739

- Rochlitz I (2003a) Study of factors that may predispose domestic cats to road traffic accidents: Part 1. Veterinary Record 153, 549–553

- Rochlitz I (2003b) Study of factors that may predispose domestic cats to road traffic accidents: Part 2. Veterinary Record 153, 585–588

- Rochlitz I (2005) Housing and welfare. In: The Welfare of Cats, ed. I Rochlitz, pp. 177–203.

- Springer, Dordrecht Seawright A, Casey RA, Kiddie J et al. (2008) A case of recurrent feline idiopathic cystitis: the control of clinical signs with behaviour therapy. Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research 3, 32–38

- Woods M, McDonald RA and Harris S (2003) Predation of wildlife by domestic cats Felis catus in Great Britain. Mammal Review 33, 174–188